The Tinkerer

As a young boy, much to his dismay, John Katsoudas (M.S. PHYS ’03) had a clearly defined role in the family business. It started with wrapping doughnuts.

His father, a restaurateur, had a contract to make 20,000 donuts for Chicago Public Schools. Young Katsoudas was the only one who could operate the machine that could wrap them. So that’s what he did for three days every summer.

“I hate doughnuts, I cannot tell you, I hate doughnuts,” Katsoudas now says. When anything broke at Sunny Donuts, Katsoudas’s father would wake him up at 3 a.m. to repair it. The pre-teen would stumble to a hardware store on Chicago’s South Side where the white-haired gearheads behind the counter would barrage him with advice, most of it good. At night he’d take apart the machines, numbering each of the hundreds of pieces so he could eventually put them together again.

“My dad couldn’t build a bookshelf if his life depended on it,” Katsoudas says. “The first time I put my hand on 120 Volts (of electricity) was at age 12.”

Now Katsoudas is messing with electricity again, co-inventing a fuel he hopes will save the world. He acknowledges the uphill battle, but says he’ll tackle it with the determination he earned growing up on Chicago’s South Side.

“The poor kid never got any sleep,” remembers his sister, Stella Katsoudas, a rock singer who sang under the stage name Sister Soleil, releasing multiple albums with Universal Records.

As a teen, John dreamed of making it big in music—or science. In high school he played drums in a band with his sister, hitting clubs across Chicago. But when he enrolled at Illinois Institute of Technology, he learned to love physics.

“I told Stella, ‘I can’t give up physics for this,’” John says.

But he almost did. He accompanied his sister on tour in her early years, managing her sound and lighting. After getting his bachelor’s degree, Katsoudas traveled to Burbank, California, to build a recording studio, sleeping on the concrete floor of the construction site for months. In time, Glenwood Place was built, but the founding partnership suffered, and dealing with recording artists grew to be more work than it was worth.

“Those guys worked their butt off building that studio, around the clock all the time,” says Edward Colver, a renowned punk rock photographer who shot more than 500 album covers and traveled to the Burbank studio often. “But his science…I think he had a life-long interest in that.”

“I never, ever intended to give up physics,” John says. So he got in contact with Duchossois Leadership Professor Carlo Segre, a physics professor at Illinois Tech who brought him back into the physics program. And later, once he earned his master’s degree in 2003, Segre offered John a job as a beamline scientist for Illinois Tech at Argonne National Labs.

While there, John was in charge of building research beamlines, first for the National Nuclear Safety Administration, then later for the broader materials science community.

But what he really liked doing was tinkering.

“I’m a first principle builder. I can build anything based on first principles,” John says. “That’s what physicists do. They’re all first principle builders, they just don’t know it.”

“John was always building something. And he was really good,” Segre says, noting Katsoudas’s various side projects, from a doughnut counter as an undergrad to an “open source” respirator during COVID-19. Segre respected his colleague’s ingenuity so much that when John and his wife, Illinois Tech Research Associate Professor Elena Timofeeva, left Argonne to start their own business, he partnered with them.

The trio’s business, Influit Energy, has literally grown tenfold—from a 2,000-square-foot research space in Chicago’s West Loop neighborhood to a 20,000-square-foot industrial space in the city’s Kinzie Industrial Corridor.

Their goal is simple: to build a liquid-based electric battery to replace petroleum, that will be safer and easier to implement than the lithium-ion model.

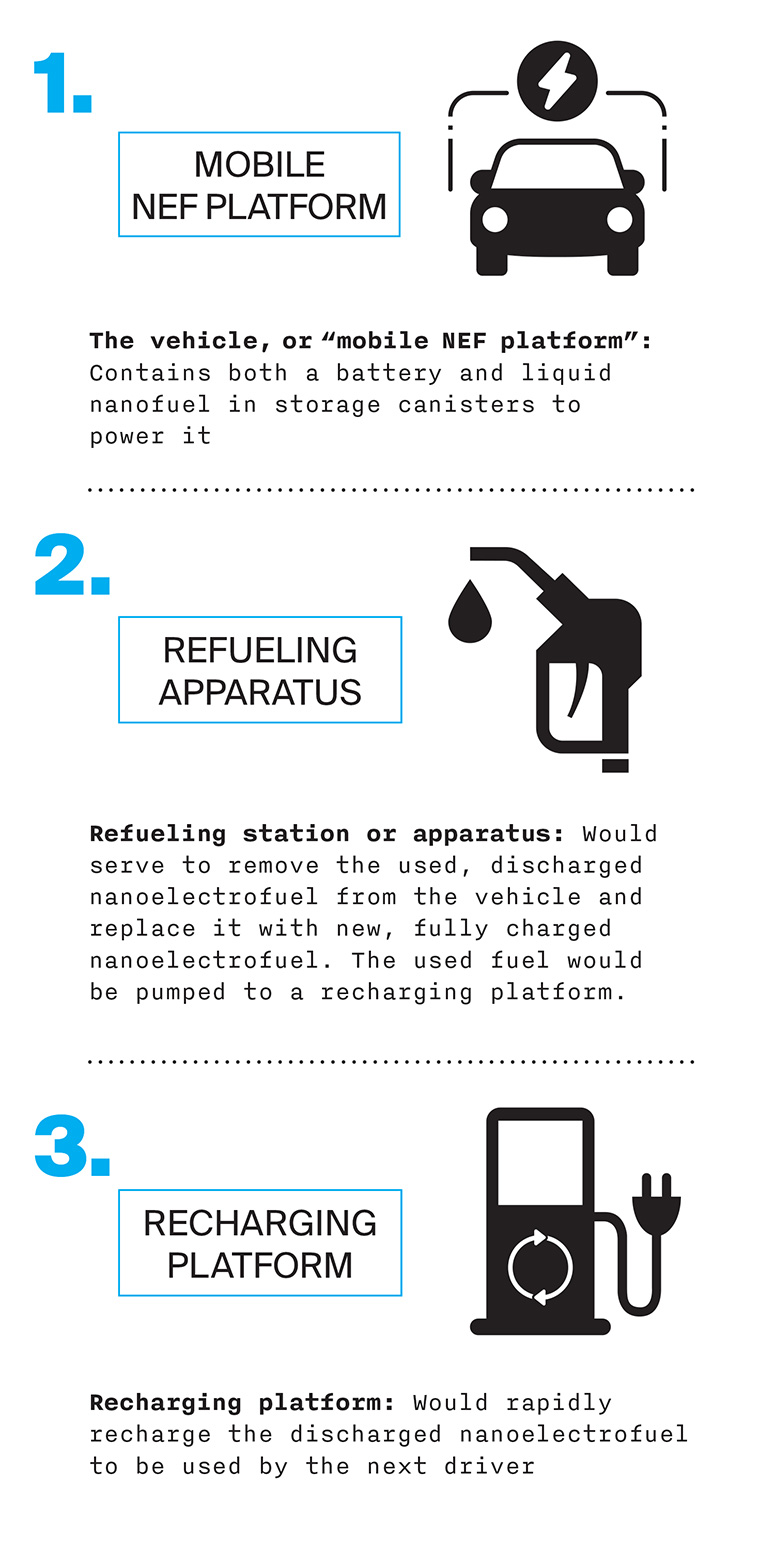

The battery relies on a fluid that contains billions of electrically charged nanoparticles, yet has a low enough viscosity to flow like water. Thus its name: nano-electrofuel(NEF).

Rather than wait to charge the battery, an operator could just replace discharged fluid, which would be left to recharge and then fuel the next vehicle. Compared to a lithium-ion battery, John says, it’s not flammable, not explosive, and does not require drivers to wait longer than the several minutes they currently do to fill their tanks.

“We put fires out (with the liquid),” John says. Plus, his battery relies on chemicals and elements that are “Earth abundant,” not limited to certain areas of the world, eliminating the need to negotiate mining or materials with foreign entities.

He’s garnered developmental contracts and is currently testing the battery on an electric utility vehicle built by a Minneapolis company; a light tower for the United States military; and a Humvee.

“Is this viable for 100 percent penetration? Yes, because people want it,” John says. “My day consists of strategizing, lots of meetings with sponsors. And do my own experiments when nobody’s looking.”

He’s traveled to Texas to meet with gas industry executives, because, he says, “the petroleum industry is the 800 pound gorilla that will fight for their markets. But they seemed receptive.” In particular, they seemed to like his technology’s potential ability to repurpose the industry’s infrastructure to transport what is essentially a rechargeable liquid fuel.

“I believe strongly that the biggest existential threat to our species is global climate change.…I’ve dedicated my life after leaving the music industry to science. But not science for science’s sake—for the betterment of the world,” he says.

For his wife and business partner, John is like a walking battery himself. “I do have my weak moments. When I’m tired, he’s always like, ‘You got it.’ He brings you to where you’re seeing through the minutia,” says Timofeeva, Influit’s Chief Scientist and Director of R&D.

John chalks it all up to Chicago “South-Side persistence.” The two still live there—Katsoudas says he isn’t comfortable anywhere else.

“My dad taught me if you want something, go do it. Make it,” he says. “If you work hard and do something, this is the place to get it done.…You just have to tune out how much work it is.” •