In the fall of 1957, two girls in their sophomore year at Little Rock Central High School in Little Rock, Ark., passed notes to each other across the aisle of their classroom. Gloria’s note read, “Becky, I see you in the hallway, but I don’t know if you want me to say hello or not.” Becky’s response expressed more than a case of new-school-year nervousness. “Gloria, I see you, too, but please, don’t say hello to me,” the note read. “The white citizens’ council has spies everywhere and I don’t want to put my family in danger.”

Although it had been more than three years since the United States Supreme Court ruled on the unconstitutionality of racial segregation in public schools with the Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka decision of May 17, 1954, Arkansas Governor Orval E. Faubus resisted the ruling, which was to begin at the high-school level in the Little Rock School District (LRSD). On September 23, 1957, nine African-American students, including 14-year-old Gloria Ray, now Gloria Ray Karlmark (CHEM, MATH ’65), decided to rightfully claim what the Supreme Court said was theirs. Against a crowd of some 1,000 protestors, they entered the all-white high school and into the chronicles of history.

Turmoil-filled Years

Karlmark never expected the ugly reception she and the other “Little Rock Nine” experienced that day, or that by a direct order from Governor Faubus, the Arkansas National Guard would bar them from entering school on the first day of class, September 2, 1957. According to Karlmark, Arkansas of the 1950s was generally considered to be more progressive than other states, such as Alabama and Mississippi, and had already lifted its ban on such laws as those that relegated African Americans to the rear of buses.

“We lived in neighborhoods that were integrated; I had white neighbors,” explains Karlmark, who visited Main Campus of Illinois Institute of Technology in May to receive the IIT Alumni Medal. “I grew up with white kids and they grew up with me. We went to different schools, but we played together. No one expected what happened because people knew one another.” African-American students in Little Rock attended Dunbar High School, which had a good academic reputation but had fewer course selections and classrooms than Little Rock Central, and lacked an athletics practice field.

Shortly after the Supreme Court decision was made, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People went before the LRSD to begin integration. Karlmark’s historic walk was delayed for two years as various strategies were initiated to prevent integration from happening. The LRSD immediately adopted the Blossom Plan, which called for gradual integration—to begin in high schools in 1957 and to be followed by grade schools in subsequent years. In early 1957, the Arkansas State Legislature continued to block integration by approving four ‘segregation bills’ and instituting a 3 percent sales tax on the election ballot to ensure that funds would be available to continue its efforts. Citizens groups, such as the Mother’s League of Central High School and the Capital Citizens Council, joined in the protest by placing anti-integration advertisements in newspapers and holding rallies. One month before school was scheduled to open, the governor of Georgia gave his support to Faubus, going so far as to commend those who supported a concept known as “state’s rights,” that is, the right of a state to oppose the federal government.

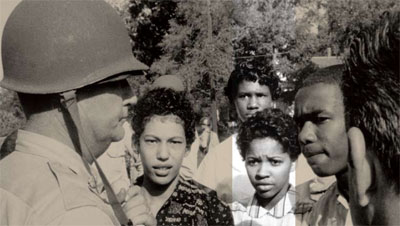

After Karlmark and her classmates were denied entrance to Little Rock Central on September 2, federal judge Ronald Davies ordered integration to begin two days later. Again, on September 4 the way was blocked for African-American students. As increased chaos ensued, Davies began legal proceedings against Faubus and several guardsman for interfering with integration. The rioting that occurred once the Little Rock Nine finally entered the school on September 23 was so intense that President Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered in units from the United States Army’s 101st Airborne Division to help restore calm. Troops remained on campus for nearly one month to escort the nine throughout their school day.

Once the troops left, the problems returned and remained with the Little Rock Nine until the end of the academic year. Only one student in the group graduated from Little Rock Central before the school was officially closed for 1958-59 after Faubus signed into law a bill that allowed him to shut down a district school that was facing integration, pending a public vote.

Because of the many traumatic experiences Karlmark endured at Little Rock Central, it was well into adulthood before she could speak openly about her time at the school. “During that year, the nine of us didn’t share with each other our problems,” she says, noting that each of them was assigned to separate classrooms, only getting together for lunch. “At the end of the day we’d say, ‘It was okay’ or ‘I managed.’ We were trying to keep up our morale and not say anything that was going to make somebody decide not to come back,” explains Karlmark. “We didn't want to worry our parents so we just kept it in.”

The nine suffered physical and mental abuse, as did those who associated with them. Karlmark recalls the kindness of Becky, who passed notes with her so many years ago. She shares what Becky meant in presentations she gives about bullying and the ‘silent majority’ to grade school children in Sweden, where she has lived for more than 40 years with her husband, Krister (M.S. DESG ’69), a former IIT Institute of Design faculty member.

“Becky couldn’t say hello to me in the hallway, but she did show friendship to me in the classroom. She did what she could do,” says Karlmark. “I tell the kids not to sit back and watch it and talk about it. There’s bound to be some little thing, however little it might seem in your mind, that you can do to improve conditions. What Becky considered as just a little thing, for me, was my whole world. She was the only kid in any class I had who saw me. I used to look forward to that class because there would at least be one person who saw me as a fellow human being who bled when hurt and who had feelings.”

Karlmark acknowledged that while the majority of students weren’t cruel, most simply didn’t “dare to object to what was wrong.” One student stood out because she did object. Robin Wood, the daughter of a local journalist, was openly friendly to each of the Little Rock Nine. “She and her family were treated exactly as we were,” recalls Karlmark. “The difference was she didn’t have a soldier escorting her between classes—she was on her own. That took real courage.” A few years before the 50th anniversary of the Little Rock Nine on September 25, 2007, Karlmark was asked what she would like inscribed at the foot of a statue made in her likeness. Her answer? “Dare to object to prejudice and injustice.”

Value of Education

With Little Rock Central shuttered for the 1958-59 academic year, Karlmark traveled to Missouri to live with her uncle and to attend the newly integrated Kansas City Central High School, where she was placed in the Advanced Studies Program. “It was a wonderful school,” says Karlmark. “It was that school that led to my coming to IIT.” Encouraged by her female chemistry teacher to apply to the university, Karlmark did and stepped into a realm of new possibilities.

“IIT taught me how to go about learning,” she says, explaining that with this skill, she was able to smoothly transition from a multifaceted technology career to a new one as a patent attorney. Upon her graduation, Karlmark spent four years at IIT Research Institute, where she worked as an assistant mathematician on the Automatically Programmed Tools IV Project. After taking a year’s sabbatical, Karlmark and her husband immigrated to Sweden, where she joined the IBM Nordic Laboratory and in 1975, completed the company’s Patent Examiner Program, moving into its international patent operations as a European patent attorney. In 1976, Karlmark cofounded the international journal Computers in Industry, serving as its editor-in-chief for 15 years. Before her retirement in 1994, Karlmark worked as a management specialist for Philips International, traveling to many countries in Europe.

The IIT Alumni Medal is just one of many honors Karlmark has received over the years. She and the Little Rock group have been commemorated on a postage stamp and a silver dollar, and memorialized in a bronze statue displayed on the grounds of the Arkansas State Capitol. In 1999, the nine visited the White House, where President Bill Clinton bestowed upon them the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest form of civilian recognition. Little Rock Central High School, still part of the LRSD, is now a National Historic Site. Mother of two children—Elin, a marketing strategist, and Mats, an IT communications specialist—Karlmark wishes her own parents were alive to see the direction her life has taken since she walked up the steps of Little Rock Central. “It was totally beyond the realm of possibility,” she says. “I take it as another tribute to how great the United States is.”

The Little Rock Nine established a foundation to hold in the public’s memory their actions that September day and to provide scholarship and mentorship for youth in poor-performing school districts. Nine high school students from around the country were selected to receive $10,000 scholarships at the 50th anniversary commemorative event, including Lindsey Brown, now a second-year physics major at Fisk University. One of only a few African-American students at her elementary school in Rhode Island and, as she recalls, the only African-American student in her fifth-grade class, Brown says that she was strengthened by the story of the Little Rock Nine during that time. “I did not face the adversity that they faced, but I do understand the discomfort they must have felt,” she explains. Because of the distance that separates them, Brown and her mentor, Karlmark, have relied upon electronic communication. “This has been one of the greatest experiences of my life,” says Brown. “I will forever cherish the emails and personal relationship with Mrs. Karlmark.”

By means of scholarship and mentorship opportunities, the Little Rock Nine are continuing the legacy passed down to them by their parents and educators who helped them keep alive their dream of bettering themselves through knowledge. “We were willing to die inside that school,” says Karlmark, who explains that while it was her desire to obtain the best learning opportunities that she could, when she stepped inside Little Rock Central, her desire matured into something more: a principle. “It was the principle of being an American citizen, not a second-class American citizen but children of one and the same God, not children of a lesser god,” she says. “I was brought up that education was the way of the future.”