“A new paradigm of long and narrow urban landscape projects are finding opportunistic lines through cities. These landscapes often go through many neighborhoods to create a kind of social highway. With Providence City Walk we were looking at a problem that many cities are investigating: the consequences to neighborhoods of road building in the latter half of the twentieth century,” says Ron Henderson.

City Walk was recognized with the Honor Award for Planning and Analysis from the American Society of Landscape Architects–Rhode Island and the Preservation Initiative Award from the Providence Preservation Society.

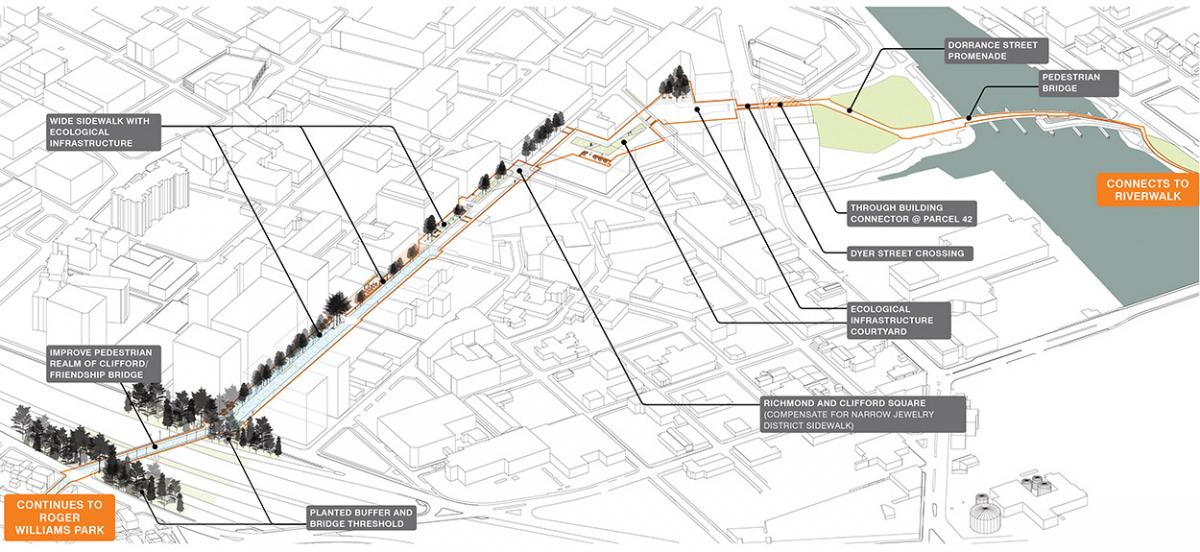

Image credit: Ron Henderson / L+A Landscape Architecture

W

hen Ron Henderson left the architecture firm where he was working in the early 1990s to study landscape architecture, he told his boss that he wanted to discover what the dirt told him he should build. “I’ve always had that instinct that a bounded project, a building, simply could not engage the world at the scale that I wanted a project to engage,” he says. Since then he has designed landscapes around the world—China, France, and North America—and is a noted expert on Chinese and Japanese gardens. Henderson’s multiple award-winning projects include the gardens of the Chinese Pavilion for the Shanghai Expo 2010, Yinzhou Park (China), Memorial to the Abolition of Slavery (France), Gardens of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, and, most recently, Providence City Walk in Rhode Island. His firm, L+A Landscape Architecture, is currently working to give new life to the historic town spring in Newport, Rhode Island, a Superfund site that is being returned to public use for the first time in 350 years. Director of Illinois Tech’s Landscape Architecture program, Henderson describes some of his favorite landscapes and shares his thoughts on the intersection of humans and the nonhuman world.

If you ask me which building is my favorite, it’s easy: the Pantheon in Rome, a building as an architect I had studied for years. No question. The first time I walked in, there was a light rain falling through the oculus into a puddle of water that captured the reflection of the sky. My knees got weak. It is such a powerful space. With landscapes, I don’t know that I could pick just one. Maybe it’s sentimental, but I still like the forests where I grew up, in southern Indiana. They weren’t natural forests; they were human managed. What’s striking to me is that I’m not picking a clearly bounded space—Central Park or the South Garden at the Art Institute, which is spectacular; or Caldwell’s Lily Pool in Lincoln Park, which is just a terrific garden; or the Lingering Garden in Suzhou; or Zuisen-ji in Kamakura.

Something we work hard to do in our landscape architecture program is to build an understanding in our students that we are a species, just like everything else. It’s not a nature-culture binary; we’re actually just part of whatever it is that we are in our existence. There are two terms in Japan—ningen bunka and zhizen bunka—one is the culture of people and one is the culture of nature. They are distinct but they are both cultures. Many cultures and individuals continue to struggle with that sense of integration of the human species into the presence of the other species, when it’s really just part of the same thing—not apart. This bias of the human condition has profound impacts on the world.

Many of the twentieth-century landscape architects in the United States grew up in rural areas or on farms, as I did. That has changed in the same way that the demographics of America have changed. Now, our students are predominantly suburban or urban, and I think they’re drawn to the profession through the social implications of public space and community building in addition to the environmental and social justice aspects of landscape architecture. I am hopeful to see how the urban environments of our contemporary generation of students will affect their work and advance the authority of landscape architects as the leaders of designing cities in the twenty-first century.