Tactical Engineering - Yesterday

It was a scene that could have been out of a James Bond flick. A man knew he had been selected to participate in a top-secret mission and was given a train ticket to Chicago’s Union Station.

Once at the station, he was to make a telephone call for instructions. The voice at the other end of the phone told the man to stand in a certain area of the station holding a newspaper under his left arm. He would then be approached by another man, who would ask him if he were waiting for someone to pick him up. If his response was “yes,” the man with the newspaper was to give his companion a designated telephone number, which was the password to their final destination, place unknown to the man with the newspaper.1

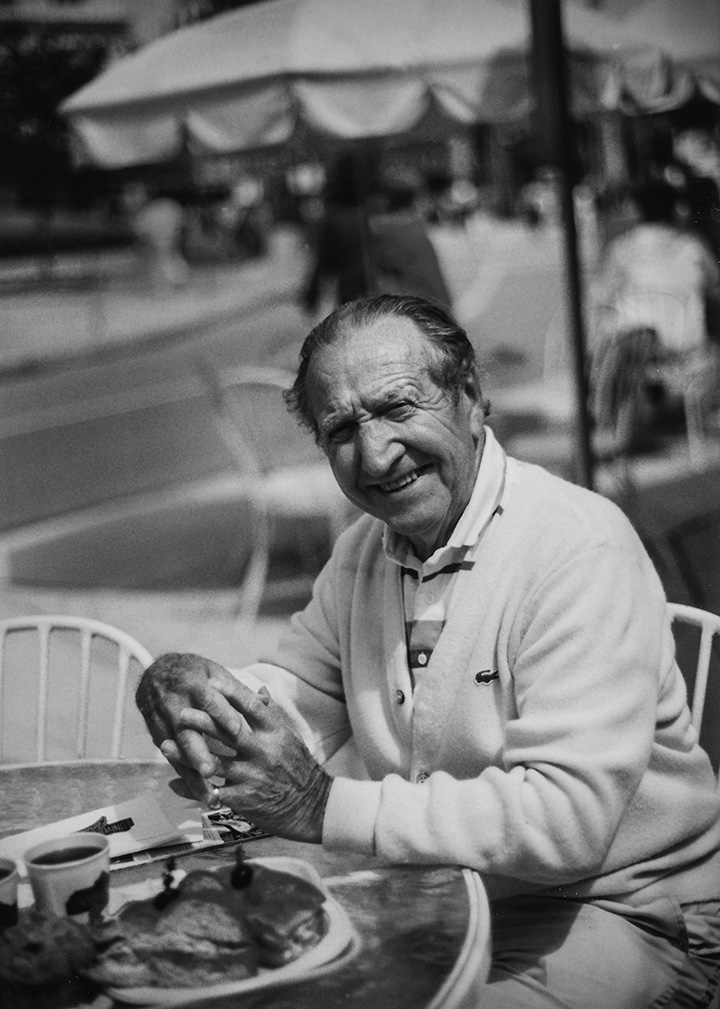

That man was Harris Harold Levee (ME ’49), who, in 1945, was sent from his post as a United States Army private at Fort Belvoir, Va., to Chicago to assist on a government mission so significant that he would not even be able to contact his family while he was on it. As Levee found out, he was on his way to the University of Chicago to work on the government’s research effort to produce the first atomic bombs: the Manhattan Project.

“I’m 95 years old and I guess that I am as patriotic as it’s possible to be because I was willing to do whatever was necessary for our country,” says the spry nonagenarian, in a phone interview from his home in Gaithersburg, Md. “I didn’t know if I was going to become full of radiation, but I did it anyway.”

Levee was selected for the Manhattan Project because he had trained as a combat engineer once drafted by the Army and had achieved very high scores on a mechanical aptitude test. He was commissioned to serve as an engineer and was also responsible for maintaining project secrecy and obtaining project patent rights from scientists such as Enrico Fermi and Leo Szilard. Levee recalls that Fermi was easy to get along with but that Szilard was one tough but brilliant character. Initially, Szilard did not wish to relinquish his patent rights, so Levee made a bold suggestion to his boss, Lieutenant Colonel Herbert E. Metcalf: Don’t pay Szilard until he does so.

“I don’t know if that’s what they did,” he says with a gleeful giggle. “But a few weeks later, Szilard signed his papers.”

While being a member of the A-bomb team may have been the high point of his life, Levee says there are other high points, such as his consulting role for the building of the first air-transportable nuclear power plant to Antarctica and his supervisory role on the construction of the model of the world’s first operational nuclear-powered submarine, the USS Nautilus.

“I didn’t know if I was going to become full of radiation, but I did it anyway.”

“I remember that the father of the nuclear submarine [popularly known as the “Father of the Nuclear Navy”], Admiral Rickover [U.S. Navy Admiral Hyman G. Rickover], visited the plant and was supposed to be the first one to start the nuclear submarine,” says Levee. “I convinced the general manager that I should be the one to see if it would, in fact, start. So I turned on the nuclear reactor, it worked, and I turned it right off, putting the control rods immediately back in so that Rickover could start it and let it run.”

Levee says his most fulfilling high point took place in India, where he supervised the construction of several coal-fired electric-generating stations in New Delhi and Takhar in the early 1960s.

“We used medieval equipment—and when I say medieval, I mean medieval—using shovels and hoes, and mixing cement by hand,” explains Levee. “To build these stations, we used about 50 tribal women to carry bowls of cement and concrete blocks on their heads, who then walked up an incline plank to dump the cement into a container. It was remarkable and absolutely amazing for someone from the United States to see and to supervise. When they fed their babies breast milk, they had to go underneath our construction site to do so.”

As much as Levee relished his consulting projects, in 1967 he responded to an advertisement in the New York Times that he felt described him perfectly. A few weeks later, he accepted a position with Norair Engineering, Inc. as vice president and resigned from the company seven years later to form his own company, Halco Engineering, Inc.

Now, Levee spends his days reading the Washington Post and relaxing with his wife, Pearl, who accompanied him to India for his engineering projects. He says that even though he came to IIT after his work on the Manhattan Project, the knowledge he received at the university added to the significance of his engineering career.

“Besides the fact that I enjoyed the teachers, who were very good, one of them, Bill Goodman, taught a graduate course in air-conditioning that I used because I eventually entered into such a business [Halco],” he says. “That course ended up being very instrumental in my future life.”

More Online

1Harris Harold Levee, interview by Cynthia C. Kelly, president, Atomic Heritage Foundation; interviewed conducted in Maryland on October 28, 2011: manhattanprojectvoices.org/people/harris-harold-levee

Manhattan Project: energy.gov/management/office-management/operational-management/history/manhattan-project