Forty-five years ago this October 23, a missile-shaped, pearlescent-blue rocket car roared down the Bonneville Salt Flats in Wendover, Utah, and into the record books because a derring-do band of technically brilliant car enthusiasts, IIT engineering students and their professors, and one highly regarded academic visionary—energy researcher Henry R. Linden (Ph.D. CHE ’52)—believed that it could. Named for the color of ignited liquefied natural gas (LNG) that served as fuel for the vehicle, The Blue Flame (TBF), driven by Gary Gabelich, blew away the existing land speed record (LSR) set in 1965 by 30 mph.

A Real Blast from the Past

-

The Blue Flame

The Blue Flame

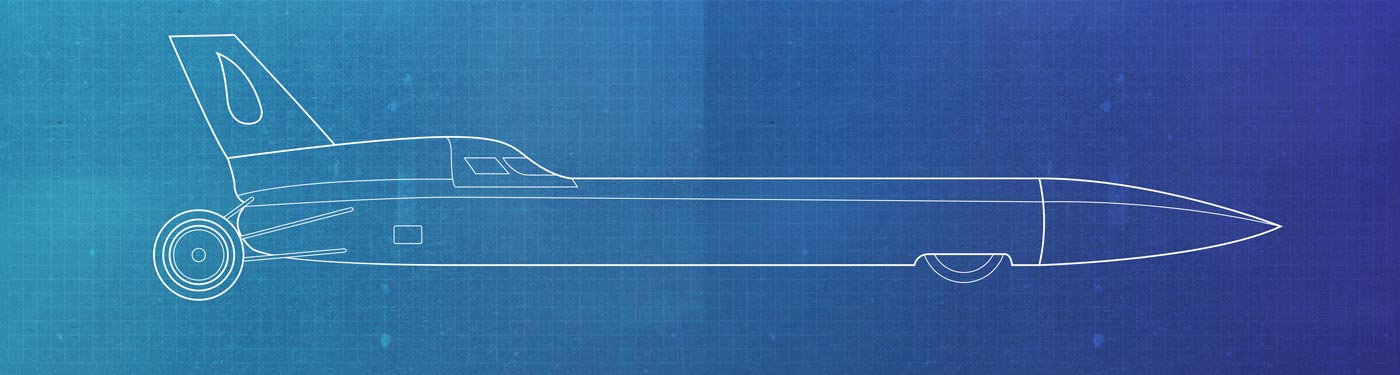

A unique set of structural, aerodynamic, and mechanical features developed by Reaction Dynamics, Inc. and Illinois Tech worked in concert to shoot The Blue Flame down the Bonneville Salt Flats not once, but twice. According to rules established by the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile, the average speed was calculated by the average of two runs—the vehicle needed to make a run in one direction, turn around, and make a second run in the opposite direction within one hour’s time.

Here are some of the major specs that helped to make the nearly 38-foot-long, two-ton (when empty) Blue Flame a record breaker:

-

Chassis

Chassis

The central chassis structure beginning at the rear of the nose cone was a riveted, stressed aluminum skin over aluminum ring structures and aluminum I-beam longerons, or stringers, similar to what is used in the construction of an aircraft’s body.

-

Wheels and Tires

Wheels and Tires

A triangular wheel layout with the front wheels one-inch apart inside the fuselage and the rear wheels seven-feet apart provided roll stability and moved the aerodynamic center of pressure rearward. The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company individually tested the wheels and tires at more than 850 mph; however, in 1970 the company required that the maximum speed be kept below 700 mph.

-

Body

Body

The Blue Flame was designed to operate in the supersonic realm above Mach 1. The most critical part of the aerodynamic design was to provide vehicle stability through the estimated transonic speed transition of Mach 0.9 through Mach 1.1.

-

Nose

Nose

The nose shape was a Von Kármán ogive (roundly tapered end) to avoid separation of the airstream at Mach speeds.

-

Fuselage

Fuselage

The fuselage cross-section was a tri-oval shape with the “V” pointing toward the ground. This was to avoid lift from any shockwaves deflected upward from the ground surface.

-

Vertical Tail Fin

Vertical Tail Fin

The vertical tail fin added to the vehicle’s stability much like the feathers on an arrow.

-

Braking System

Braking System

Parachutes and disc brakes were used to stop the car. At high speed the first parachute was deployed by a slug fired by compressed air projecting a small pilot parachute, which then pulled the high-speed parachute from its housing. At 300 mph the driver then released a larger, low-speed parachute and finally applied the wheel brakes (rear wheels only) at 100 mph to come to a stop. A second complete parachute system provided redundancy.

-

Propellant System

Propellant System

The nose cone held two titanium spheres with high-pressure air for pressurizing the hydrogen peroxide tank and a smaller fiberglass-reinforced sphere containing helium for pressurizing the cryogenic liquefied natural gas (LNG) tank. Behind the front wheels a large stainless steel tank held the hydrogen peroxide propellant and a smaller aluminum tank contained the LNG propellant, which were pressurized to 600 psi. The rocket motor, plumbing, control valves, parachute canisters, and various accessory hardware pieces of equipment were behind the cockpit. The Blue Flame carried a fuel load of five gallons of LNG and 180 gallons of hydrogen peroxide.

“The Blue Flame’s 630.478 mi/h (1,014.656 km/h) record speed in the kilometer remains the fastest ever at the Bonneville Salt Flats; the 1,014 km/h record speed was the first record over 1,000 km/h and resulted in much acclaim throughout Europe,” says Dick Keller, who was a chief technologist at IIT Research Institute when he and colleague Ray Dausman developed their idea for the X-1 rocket dragster, the prototype to TBF, in the mid-1960s. “The 622.407 mi/h record speed in the mile lasted 13 years. The 1,014.656 km/h kilometer record speed lasted 27 years.”

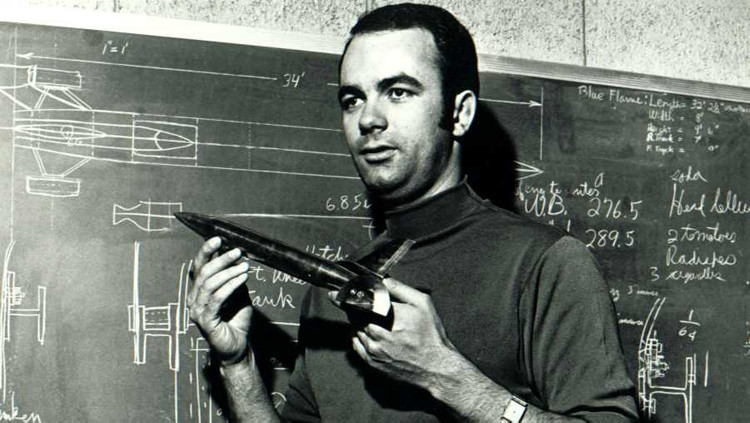

Dausman (who originally suggested using a rocket to power TBF but left the project before the car went to the salt flats) and Keller enlisted the services of dragster builder Pete Farnsworth to form Reaction Dynamics, Inc., the core team that designed and fabricated the vehicle. Keller presented the concept to Linden, then president of the Institute of Gas Technology, an IIT affiliate; Linden subsequently obtained funding for the vehicle from a large group of American natural gas industry supporters. Linden also enlisted a cadre of talented IIT students led by faculty members T. Paul Torda and Sarunas C. Uzgiris (M.S. ME ’63, Ph.D. MAE ’66), who refined the aerodynamic qualities of the car by incorporating a specially designed nose for low drag, triangular body cross-section shape, and slight nose-down body slant.

The Blue Flame, now displayed at Germany’s Auto & Technik Museum Sinsheim, primed the possibility that LNG could be utilized as a clean transportation-fuel alternative, an option still being researched today. And the insatiable desire to surpass world-record speed also continues, as two groups—a British team and team Aussie Invader 5R from Australia—are working to achieve 1,000mi/h in 2016 in Hakskeen Pan, a dry lakebed in South Africa’s Northern Cape province.

Driving with One Hand - Video Extra

Members of The Blue Flame crew and Illinois Tech’s Henry R. Linden Professor of Energy share memories of the day the rocket car broke the land speed record and note the added significance of the achievement.

“The Blue Flame has always been my favorite LSR car not only because she was really slick and pretty—boasting the best technical backing of any project ever before or since 1970—but also because The Blue Flame team [members] were total professionals,” says drag-racing record holder Rosco McGlashan, who is already the ‘Fastest Aussie on Earth’ and has been working to become the fastest man on Earth for more than 50 years.

“Richard Keller has been a godsend to our project assisting us with design ideas and rectifying construction problems we had to overcome. My team is building a car with a 62,000-lbf [pound-force, or pounds of thrust] bi-propellant motor; it has often been referred to as ‘The Blue Flame on Steroids.’ We’ve had some real highs and heaps of real lows but [what] keeps us motivated are the achievements the pioneers before us have won, including the great work Illinois Institute of Technology did back then. Their research is our bible.”